Red-eye effect

The red-eye effect in photography is the common appearance of red pupils in color photographs of eyes. It occurs when using a photographic flash very close to the camera lens (as with most compact cameras), in ambient low light. The effect appears in the eyes of humans and animals that have no tapetum lucidum, hence no eyeshine, and rarely in animals that have a tapetum lucidum. The red-eye effect is a photographic effect, not seen in nature.

Contents |

Causes

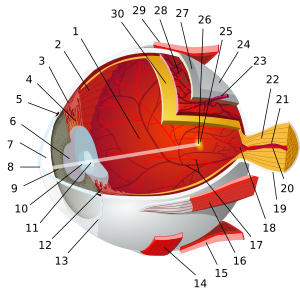

Because the light of the flash occurs too fast for the pupil to close, much of the very bright light from the flash passes into the eye through the pupil, reflects off the fundus at the back of the eyeball and out through the pupil. The camera records this reflected light. The main cause of the red color is the ample amount of blood in the choroid which nourishes the back of the eye and is located behind the retina. The blood in the retinal circulation is far less than in the choroid, and plays virtually no role. The eye contains several photostable pigments that all absorb in the short wavelength region, and hence contribute somewhat to the red eye effect [1]. The lens cuts off deep blue and violet light, below 430 nm (depending on age), and macular pigment absorbs between 400 and 500 nm, but this pigment is located exclusively in the tiny fovea. Melanin, located in the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and the choroid, shows a gradually increasing absorption towards the short wavelengths. But blood is the main determinant of the red color, because it is completely transparent at long wavelengths and abruptly starts absorbing at 600 nm. The amount of red light emerging from the pupil depends on the amount of melanin in the layers behind the retina. This amount varies strongly between individuals. Light skinned people with blue eyes have relatively low melanin in the fundus and thus show a much stronger red-eye effect than dark skinned people with brown eyes. The same holds for animals. The color of the iris itself is of virtually no importance for the red-eye effect. This is obvious because the red-eye effect works best when photographing dark adapted subjects, hence with fully dilated pupils. Photographs taken with infra-red light through night vision devices always show very bright pupils because, in the dark, the pupils are fully dilated and the infra-red light is not absorbed by any ocular pigment.

The role of melanin in red-eye effect is nicely demonstrated in animals with heterochromia: only the blue eye displays the effect. The effect is still more pronounced in humans and animals with albinism. All forms of albinism involve abnormal production and/or deposition of melanin.

Red-eye effect is seen in photographs of children also because children's eyes have more rapid dark adaption: in low light a child's pupils enlarge sooner, and an enlarged pupil accentuates the red-eye effect.

In a photograph of a child's face, red-eye in one eye but not the other may be a sign of the cancer retinoblastoma.

Similar effects

Similar effects, some related to red-eye effect, are of several kinds:

- In many flash photographs, even those without perceptible red-eye effect, many animals' pupils display eyeshine. Although eyeshine is an unrelated effect, animals with blue eyes may display the red-eye effect in addition to eyeshine.

- Numerous diseases of the eye cause a "white-eye effect" instead of the expected red-eye effect (see Leukocoria).

- A related effect, red reflex, is seen in fundoscopy; unlike the red-eye effect, it is not a photographic effect.

- In photographs recorded with infrared-sensitive passive (non-IR emitting) equipment, the eyes (not only the pupils) usually appear very bright. This is due not to reflection, but to radiation of core body heat in the form of infrared light (see Night vision).

Photography techniques for prevention and removal

The red-eye effect can be prevented in a number of ways. [2]

- Using bounce flash in which the flash head is aimed at a nearby pale colored surface such as a ceiling or wall or at a specialist photographic reflector. This both changes the direction of the flash and ensures that only diffused flash light enters the eye.

- Placing the flash away from the camera's optical axis ensures that the light from the flash hits the eye at an oblique angle. The light enters the eye in a direction away from the optical axis of the camera and is refocused by the eye lens back along the same axis. Because of this the retina will not be visible to the camera and the eyes will appear natural.

- Taking pictures without flash by increasing the ambient lighting, opening the lens aperture, using a faster film or detector, or reducing the shutter speed.

- Using the red-eye reduction capabilities built into many modern cameras. These precede the main flash with a series of short, low-power flashes, or a continuous piercing bright light triggering the iris to contract. (This should not be confused with the autofocus assist beam, which uses a series of flashes for focus instead.)

- Having the subject look away from the camera lens.

- Increase the lighting in the room so that the subject's pupils are more constricted.

- Some computer digital image editors have the ability to lessen the red eye by desaturating the red color.

If direct flash must be used, a good rule of thumb is to separate the flash from the lens by 1/20 of the distance of the camera to the subject. For example, if the subject is 2 metres (6 feet) away, the flash head should be at least 10 cm (4 inches) away from the lens.

Professional photographers prefer to use ambient light or indirect flash as the red-eye reduction system does not always prevent red eyes, for example if people look away during the pre-flash. In addition, people do not look natural with small pupils, and direct lighting from close to the camera lens is considered to produce unflattering photographs.

Various graphics editing software packages have functions to remove red eyes from digital photographs. Some have automated this process, and can apply it to many photos at once. Red-eye removal is also built into many popular consumer programs like Adobe's Photoshop, Apple's iPhoto, Corel Photo-Paint, GIMP, Google's Picasa, and Microsoft Windows Live Photo Gallery. The downside to fully automatic software-based red-eye removal is that it is only accurate to approximately 75%.[3]

References

- ↑ J. van de Kraats and D. van Norren: "Directional and nondirectional spectral reflection from the human fovea" J.Biomed. Optics, 13, 024010, 2008

- ↑ Dave Johnson (2009-01-16). "HOW TO: Avoid the red eye effect". New Zealand PC World. http://pcworld.co.nz/pcworld/pcw.nsf/digi/D193D7DD8DD78628CC257540000F4A4F. Retrieved 2010-01-09.

- ↑ Raimondo Schettini and Francesca Gasparini and Fadi Chazli: "A modular procedure for automatic red eye correction in digital photos","Color Imaging IX: Processing, Hardcopy, and Applications" 5293, 139-147. SPIE, 2003

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||